Dare to be wise

“Preparatory human beings — I welcome all signs that a more virile, warlike age is about to begin, which will restore honor to courage above all. For this age shall prepare the way for one yet higher, and it shall gather the strength that this higher age will require some day—the age that will carry heroism into the search for knowledge and that will wage wars for the sake of ideas and their consequences. To this end we now need many preparatory courageous human beings who cannot very well leap out of nothing, any more than out of the sand and slime of present—day civilization and metropolitanism—human beings who know how to be silent, lonely, resolute, and content and constant in invisible activities; human beings who are bent on seeking in all things for what in them must be overcome; human beings distinguished as much by cheerfulness, patience, unpretentiousness, and contempt for all great vanities as by magnanimity in victory and forbearance regarding the small vanities of the vanquished; human beings whose judgment concerning all victors and the share of chance in every victory and fame is sharp and free; human beings with their own festivals, their own working days, and their own periods of mourning, accustomed to command with assurance but instantly ready to obey when that is called for—equally proud, equally serving their own cause in both cases; more endangered human beings, more fruitful human beings, happier beings! For believe me: the secret for harvesting from existence the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment is—to live dangerously! Build your cities on the slopes of Vesuvius! Send your ships into uncharted seas! Live at war with your peers and yourselves! Be robbers and conquerors as long as you cannot be rulers and possessors, you seekers of knowledge! Soon the age will be past when you could be content to live hidden in forests like shy deer. At long last the search for knowledge will reach out for its due; it will want to rule and possess, and you with it!”1

– Friedrich Nietzsche

Introduction

We are constantly told what to do, think or feel. Media channels are flooded with messages by groups from the world of business and politics. Thousands of experts warn us of endless dangers trying to influence our judgment, urging us to buy things we don’t need and vote for policies we don’t understand, using money and wisdom we don’t have. Only through them, we are told, can we be led to safety, happiness, and success.

“It is so easy to be immature. If I have a book to serve as my understanding, a pastor to serve as my conscience, a physician to determine my diet for me, and so on, I need not exert myself at all. I need not think, if only I can pay: others will readily undertake the irksome work for me. The guardians who have so benevolently taken over the supervision of men have carefully seen to it that the far greatest part of them (including the entire fair sex) regard taking the step to maturity as very dangerous, not to mention difficult. Having first made their domestic livestock dumb, and having carefully made sure that these docile creatures will not take a single step without the go-cart to which they are harnessed, these guardians then show them the danger that threatens them, should they attempt to walk alone.”2

Questioning the authority of the government, of experts or public opinion has always been potentially dangerous. Even questioning your own beliefs, desires and principles creates a sense of existential vertigo that may flirt dangerously close with madness.

It was questioning that led the archetypical philosopher, Socrates, to pay the ultimate price, condemned to death after his repeated attempts at improving the sense of justice of his fellow citizens, disputing collective notions like “might makes right”, and showing that those who claimed to know in fact didn’t3. Such philosophical activity eventually irritated some powerful and influential people, who brought trumped up charges against him determining his fate.

That is why from Classical antiquity to the Age of Reason and beyond, any conception of philosophy faithful to its origins required daring. For to attempt to be one’s own master, to discover for yourself the path to maturity and wisdom — is dangerous — but necessary.

To cut men’s throats, robbers rise up at night; to save your own life, won’t you wake up? Well, if you will not live wisely while health remains, be sure that you will hasten to be wise when the dropsy seizes you. And what is true of the body is true also of the soul; for, if you do not wake early, call for a light and a book, and set your mind to studious work and on wholesome thoughts, you will toss sleeplessly, tormented by evil ideas and passions. Rule your passion, for unless it obeys, it gives commands. Tell me, why are you so anxious to remove from your eyes something which may hurt them, yet are so ready to put off, year after year, the mending of your soul? Well begun is half done. Dare to be wise, begin!4

– Horace

Philosophy as conceived in classical antiquity was never just criticism, interpretation or textual commentary but an endless attempt to act on and live by the insights and principles gained via philosophical reflection, to create and improve the tools, structures, rituals, exercises and institutions that embody them and revise everything again in light of new evidence or insight.

“The Stoic Epictetus reproached his students for using the explication of texts merely to show off: “When I’m asked to comment on Chryssipus5, I do not brag; rather, I blush if I cannot display conduct which resembles his teachings and is in accord with them.””6

Unfortunately, as I wrote in the overview of the Philosophy Reborn initiative, over time this grand scope of philosophy was dismembered and emasculated till it became a shadow of itself, safe and ineffective. Philosophy as it is done nowadays cannot honor our yearning for wisdom, freedom or transcendence.

So today I’m inviting you to dare do it differently. Let us pick the abandoned banner, the distinctive feature by which it can be recognized, and also its motto, the instruction that we give to ourselves and propose to others:

Sapere aude: Dare to be wise! Have the courage, the audacity, to know — and do.

This exhortation to wisdom resonates today as much as it did in antiquity and the Enlightenment. For it takes daring to walk alone without guidance from another: “Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-imposed immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s understanding without guidance from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of understanding, but in lack of resolve and courage to use it without guidance from another. Sapere Aude! [Dare to be wise!] “Have courage to use your own understanding!” – that is the motto of enlightenment”7. It is “considered both as a process in which men participate8 collectively and as an act of courage to be accomplished personally.”

Dare to be wise today becomes not just a motto but an open invitation to a philosophical fight club and agoge of an Academy Reborn.

What is a Philosophical Fight Club and Agoge?

“It is easy to make fun; and this is justified, if philosophers do nothing but talk about the ideal of the sage. If, however, they have made the decision — which is serious and has grave consequences — truly to train themselves for wisdom, then they deserve our respect, even if their progress has been minimal. What matters is (to use Jacques Bouveresse’s formula for an idea of Wittgenstein’s) “what personal price have they had to pay” in order to have the right to talk about their efforts toward wisdom.”9

Man used to live in nature, free and wild, “but has since been tamed and subdued…[the world of advertising] has reduced [us] to a generation of spectators. We’ve been emasculated…sold a lifestyle for as long as we can remember…we have no sense of direction.”10. That is the mindset, further portrayed in the clip from the movie below, that leads the protagonists in Fight Club, to create an underground society engaged in no-holds-barred fights, a fight club, that enables them to rediscover their masculinity, strip away their fear of pain and reliance on material signifiers for self-worth, and experience feeling in a society where they are otherwise numb11.

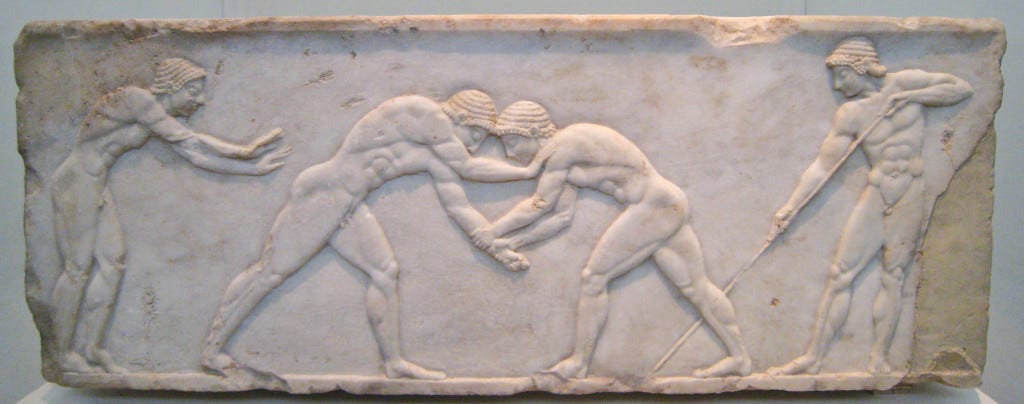

The agoge was a rigorous education and training regimen in ancient Sparta12. It aimed to create individuals that were brave, loyal, honorable, stealthy, self-sufficient, tolerant of pain, cold, hunger, and terse in speech — laconic13.

The agoge occurred in a communal setting away from family, where individuals received military training, instruction in reading, writing, poetry and dancing, and encouraged to develop survival skills, even stealing – as long as they didn’t get caught in which case they were punished. The agoge was so strict and harsh that Plutarch said of the Spartans that “…they were the only men in the world with whom war brought a respite in the training for war”14. Unsurprisingly, the agoge resulted in the most feared military force in the ancient world, “at the height of Sparta’s power – between the 6th and 4th centuries BC – it was commonly accepted that “one Spartan was worth several men of any other state”15 this belief famously vindicated at the Battle of Thermopylae, making “the term “spartan” synonymous with fearlessness, harsh and cruel life, endurance or simplicity by design.”16

The two elements described above are combined and sublimated17 to give rise to a philosophical fight club and agoge, a setting and voluntary process, where you submit your collection of fundamental beliefs, goals, methods, practices, principles and values that make up your worldview and determine your behavior, actions, decisions and your attempts to understand, explain and master the world, to tenacious criticism for the sake of improvement, in a controlled environment. It aims to be a constantly evolving regimen for those who’ve made the serious decision to truly train for wisdom and are willing to pay the personal price that gives them the right to talk about their efforts toward wisdom.

It’s a philosophical octagon, a place where we train together in philosophical pankration18—and eventually real mixed martial arts (MMA)—aspiring to become the ultimate philosophical warriors, able to understand, withstand, neutralize and turn to our advantage mental, physical, emotional and spiritual attacks irrespective of whether they aim above or below the belt.

The philosophical fight club and agoge aims to do to contemporary philosophy what MMA did to the Martial Arts. It woke them from their dogmatic slumbers and showed them to be ineffective when they weren’t protected by their own circumscribed domain of rules.

Philosophers need to wake up and get in the octagon of real life, where right serves might and the bad Eris is winning the fight, to overcome their impotence by training for both right and might, in every field relevant to the art of living.

War, Athena, and Eris

“The war of ideas is a Greek invention. It is one of the most important inventions ever made. Indeed, the possibility of fighting with words and ideas instead of fighting with swords is the very basis of our civilization, and especially of all its legal and parliamentary institutions.”19 – Karl Popper

The ancient Greek god of war, Ares, had a sister named Eris that was the goddess of chaos, strife and discord, things we tend to consider bad. However, the ancient Greek poet Hesiod, thought there were two versions of the goddess:

“As for the one, a man would praise her when he came to understand her; but the other is blameworthy: and they are wholly different in nature. For one fosters evil war and battle, being cruel: her no man loves…But the other is…far kinder to men. She stirs up even the shiftless to toil; for a man grows eager to work when he considers his neighbour, a rich man who hastens to plough and plant and put his house in good order; and neighbour vies with his neighbour as he hurries after wealth. This Eris is good for men.”20

We can visualize Eris in a sort of spectrum with the two extremities representing the two versions. I’ve included some key words above and below the two to give an illustration of the symbols, activities, values, states and emotions related to each.

The Bad Eris represents force without justice, where physical or rhetorical power is used with no regard for truth, and right serves might. It is an attitude not open to cultured dialogue:

“You cannot have a rational discussion with a man who prefers shooting you to being convinced by you. In other words, there are limits to the attitude of reasonableness. It is the same with tolerance. You must not, without qualification, accept the principle of tolerating all those who are intolerant: if you do, you will destroy not only yourself, but also the attitude of tolerance.”21

This attitude is historically exemplified by the infamous Nazi phrase: “When I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver”22.

You see, just like might is not necessarily right, right often lacks might. Neither situation is desirable. If someone is ignorant and weak, they are potentially harmful but ineffective in carrying out harm. If wise and weak, helpful but ineffective. If ignorant and powerful, potentially harmful but effective in carrying out harm. Finally, if wise and powerful, helpful and effective.

Perhaps it is in recognition of that fact that in ancient Greece, the goddess of wisdom, Athena, was also a goddess of power, courage, strength and war — but not of any war, that was her brother Ares — but the just war. In contrast to Ares, “the patron of violence, bloodlust and slaughter”23 , Athena:

“…is known for her calm temperament, as she moves slowly to anger. She is noted to have only fought for just reasons, and would not fight without a purpose…the patron goddess of heroic endeavor…she represents intelligence, humility, consciousness, cosmic knowledge, creativity, education, enlightenment, the arts & crafts, eloquence…inspiration and civilization. She stands for Truth, Justice, and Moral values. She plays a tough, clever and independent role…the opposite of Ares in combat…she represents the disciplined, strategic side of war…Athena is a goddess of war strategy, she disliked fighting without purpose and preferred to use wisdom to settle predicaments. The goddess approved of fighting only for a reasonable cause or to resolve conflict. She encouraged everyone to use intuitive wisdom rather than anger or violence.”24

However, when the war was just and necessary she became Athena Promachos — which means Athena who fights in the front line. Under the bad Eris right serves might, under the good Eris there is a revolution reflecting the nature of Athena: might serves right.

Accordingly, the “Athenian” philosopher is one who tries to be both wise and powerful, his might serving right at the front lines, beneficial and effective. Athenian philosophers have to be able to defend themselves — and win — against others who won’t play by the rules of their high ideals25 their purpose, to the extent possible, to “eliminate antagonisms without harming the antagonists themselves, as opposed to violent resistance, which is meant to cause harm to the antagonist”26.

The Two Forms of Competition: Antagonismos and Synagonismos

The good and the bad Eris find their counterpart in the two Greek words for competition. The competition associated with the former is expressed by the word synagonismos (συναγωνισμός) a word that roughly translates as “competing together with one another”. It is composed of the connective συν- which can mean “with; together; in common; completion; addition” and αγών which can mean contest, struggle, fight or game. The Olympic Games in Greek are called Ολυμπιακοί Αγώνες. To compete in this way means that together we add to something greater than ourselves that is nevertheless part of us — the game27 — thus mutually benefit.

On the other hand, the competition associated with the bad Eris is expressed by the word antagonismos (ανταγωνισμός) that roughly translates as “competing against one another”. To compete in this way means your loss is my gain — a zero sum game. I’m fighting against you, not for the game.

The spirit of the Olympic Games is that of synagonismos, what the Greeks called ευγενής άμιλλα. The first word, ευγενής, alternatively means noble, generous and polite, while the second, άμιλλα, describes the effort for supremacy between two or more persons that are pursuing the same goal and first place with motives that are primarily ethical28. Άμιλλα is connected with an admiration that motivates one to reach or surpass the object of his admiration. Ανταγωνισμός on the other hand is connected with envy and ill will that desires the loss of the object of envy from those who possess it. Eris, therefore, manifests herself in two forms, and probably at times in some form in between.

The ethos related to the good Eris can also be found in the Homeric ideal and the philosophical schools of antiquity29, the chivalric code in medieval Europe, Bushido, Aikido, Satyagraha and the ways of the Bodhisattvas in Buddhism.

The aim of Dare to be wise is to instill the ethos related to the good Eris while not remaining defenseless against the bad Eris, in either the personal, social or political sphere, whether dealing with the physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioral or spiritual dimensions.

The cursory diagram below (some titles, e.g. “Eristics”, contain working hyperlinks) is an example of a potential roadmap for creating a curriculum that accommodates the bad and the good Eris:

Get Mad and Dare

“Our greatest blessings, come to us by way of madness” – Socrates30

When Howard Beale, the character in the clip above from the brilliant 1976 film Network, exhorts us to become mad, he clearly does not mean crazy, for he used that word earlier during the clip in an derogatory manner as something that ought to be changed. The key to understanding kind of mad he wants us to become is when he says: “First, you got to get mad, you got to say, I’m a human being god damn it! My life has value!”

This kind of mad, resembles what the ancient Greeks called menos:

In the Iliad, the typical case is the communication of menos during a battle, as when Athena puts a triple portion of menos into the chest of her protégé Diomede, or Apollo puts menos into the thumos[spiritedness] of the wounded Glaucus. This menos is not primarily physical strength; nor is it a permanent organ of mental life like thumos[spiritedness] or nous[intellect]. Rather it is, like ate[infatuation], a state of mind. When a man feels menos in his chest, or “thrusting up pungently into his nostrils,” he is conscious of a mysterious access of energy; the life in him is strong, and he is filled with a new confidence and eagerness…In man it is the vital energy, the “spunk,” which is not always there at call, but comes and goes mysteriously and (as we should say) capriciously. But to Homer it is not caprice: it is the act of a god, who increases or diminishes at will a man’s arete…[and] moral courage…sometimes, indeed, the menos [being] roused by verbal exhortation”31

That is what Beale is trying to do: rouse our menos through verbal exhortation and give us the spunk and moral courage implied in asserting that, contrary to an insidious social reality where the life of the average individual is treated with no value, that one’s life does have value.

That is also what I’ve been trying to do with this text. For I too,

“…don’t have to tell you things are bad. Everybody knows things are bad…everybody’s out of work or scared of losing their job. The dollar buys a nickel’s worth. Banks are going bust. Shopkeepers keep a gun under the counter. Punks are running wild in the street and there’s nobody anywhere who seems to know what to do, and there’s no end to it. We know the air is unfit to breathe and our food is unfit to eat, and we sit watching our TVs while some local newscaster tells us that today we had fifteen homicides and sixty-three violent crimes, as if that’s the way it’s supposed to be. We know things are bad — worse than bad. They’re crazy. It’s like everything everywhere is going crazy, so we don’t go out anymore. We sit in the house, and slowly the world we are living in is getting smaller, and all we say is: “Please, at least leave us alone in our living rooms. Let me have my toaster and my TV and my steel-belted radials and I won’t say anything. Just leave us alone.”

Well, I’m not gonna leave you alone either. I want you to get mad and dare to be wise with me. “I don’t want you to protest. I don’t want you to riot — I don’t want you to write to your congressman” I want you

“to be silent, lonely, resolute, and content and constant in invisible activities; bent on seeking in all things for what in them must be overcome; distinguished as much by cheerfulness, patience, unpretentiousness, and contempt for all great vanities as by magnanimity in victory and forbearance regarding the small vanities of the vanquished; whose judgment concerning all victors and the share of chance in every victory and fame is sharp and free; with [your] own festivals, [your] own working days, and [your] own periods of mourning, accustomed to command with assurance but instantly ready to obey when that is called for—equally proud, equally serving [your] own cause in both cases; more endangered, more fruitful, happier! For believe me: the secret for harvesting from existence the greatest fruitfulness and the greatest enjoyment is—to live dangerously!….soon the age will be past when [we would] be content to live hidden in forests like shy deer. At long last the search for [wisdom] will reach out for its due; it will want to rule and possess, and we with it!”32

Let us train.

We’ve already held Philosophical Fight Clubs in Denmark, Croatia, and England. Check the trailer below and contact me if you’re interested in organizing a philosophical fight club for your company or group.

F. Nietzsche, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, section 283, translation from W. Kaufmann, The Gay Science, p.228, Vintage, 1974.

The last sentence contains a paraphrase from the Wikipedia article on Socrates, section “Trial and Death”.

Horace, Epistles, Book 1, Epistle 2. The translated text is an amalgam and slight re-ordering I made from C. Macleod, Horace The Epistles, Edizioni Dell’Ateneo, 1986, H.R. Fairclough, Horace: Satires, Epistles and Ars Poetica, Harvard University Press (Loeb), 1929, Dana and Dana, Horace: Quintus Horatius Flaccus, The Elm Press, 1911.

Chryssipus was a renowned Stoic philosopher, called the Second Founder of Stoicism.

P. Hadot, What is Ancient Philosophy, p.153.

M. Foucault, “What is Enlightenment?”, from The Foucault Reader, p.35, ed. Peter Rabinow, Pantheon Books, 1984. Other than what was put in quotes, some preceding sentences, starting from “…the distinctive feature” are paraphrased from that very page and book just mentioned.

P. Hadot, What is Ancient Philosophy, p.232, italics added.

Collated from an interview of the two lead actors, Brad Pitt and Edward Norton, who play the protagonists of Fight Club.

Collated from the Theme section of the Wikipedia article on Fight Club.

The adjective “laconic”, originates from Laconia, a region of Greece that included Sparta and “whose inhabitants had a reputation for verbal austerity and were famous for their blunt and often pithy remarks” from Wikipedia entry on Laconic phrase.

Plutarch, The Life of Lycurgus, 22.2.

From the Wikipedia entry on the Spartan Army.

From the Wikipedia entry on the Spartan Army.

Pankration was “a sporting event introduced into the Greek Olympic Games in 648 BC…an empty-hand submission sport with scarcely any rules…The term comes from the Greek παγκράτιον [pankrátion], literally meaning “all of might” from πᾶν (pan-) “all” and κράτος (kratos) “strength, might, power”” from Wikipedia entry for Pankration. Pankration was the ancient version of what today we call Mixed Martial Arts (MMA).

K. Popper, Conjectures and Refutations, p.501, Routledge, (originally published 1963) 2002.

Hesiod, Work and Days.

K. Popper, “Utopia and Violence”, in Conjectures and Refutations.

Popularly misattributed to Hermann Goering, this quote actually comes from the play Schlageter written by Hanns Johst. A more literal translation would have been: “When I hear the word culture I release the safety on my Browning!” (see Wikipedia article on Johst) but I agree with the considerations expressed by Andrew Hammel here so I went with this translation.

They are, like Odysseus, polytropoi, filled with metis, masters at answering the conundrum associated with the original sense of realpolitik as described in the Wikipedia entry for RealPolitik: “Realpolitik emerged in mid-19th century Europe from the collision of the enlightenment with state formation and power politics. The concept, Bew argues, was an early attempt at answering the conundrum of how to achieve liberal enlightened goals in a world that does not follow liberal enlightened rules…the great achievement of the Enlightenment had been to show that might is not necessarily right. The mistake liberals made was to assume that the law of the strong had suddenly evaporated simply because it had been shown to be unjust.”

Great athletes are aware of this, a good example of that awareness being Kobe Bryant’s poem “Dear Basketball” written in the occasion of the announcement of his retirement.

In Phaedrus 244a, by Plato.

Dodds, E. R. (1962-12-01). The Greeks and the Irrational (Sather Classical Lectures) (Kindle Locations 198-212 and 233-236). University of California Press – A. Kindle Edition.

F. Nietzsche, Die fröhliche Wissenschaft, section 283, translation from W. Kaufmann, The Gay Science, p.228, Vintage, 1974. With few personal alterations and omissions.